I must admit that after our long weekend in Pembrokeshire I was slightly put off…

The Tudor Garden

I must admit, I couldn’t choose which era’s of garden design I like the most. All of them have a special ambience and they all can grab my imagination. The Tudor garden is no exception. Let’s have a look what a Tudor garden looks like.

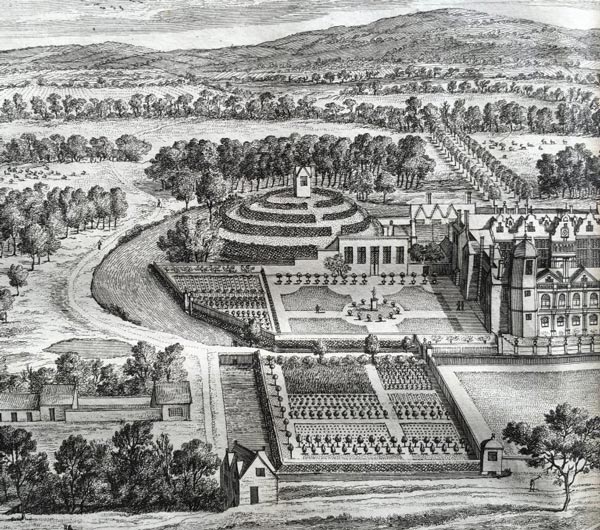

Don’t forget, this is Henry VIII’s era when everything became much bigger, showing off and megalomania described royal estates and land of the wealthy. It wasn’t any different during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign, when the nobility tried to fascinate her with trellis pavilions, rose gardens, flowerbeds, fruit trees and fountains. Doctors already realised the importance of exercise, so walking in the garden was highly recommended. (Of course, if the weather didn’t allow it, the long gallery of country houses became the scene for sports and exercising.)

Mount

Tudor gardens were still enclosed, however they became much bigger than before. In the late medieval times man-made mounts were erected which had a religious meaning and symbolise the Calvary. Of course, it could also be used to keep an eye on the surroundings and be aware what was going on outside of the garden’s walls. These mounts were often spiral (snail). There was a mount at Hampton Court and Montacute, some estates even had several mounts. Unfortunately, most of them were demolished during the history.

Banqueting houses

You can find pavilion like buildings in the corner of Tudor gardens. These are called banqueting houses and they came in all shapes and sizes. Whereas banquet today means a celebration and a main meal, in Tudor times the banquet was a final course of sweet things. The main course was always served in the hall of the country house, but once finished, guests would go to the banqueting house where sweet dishes were served. I think, banqueting houses provide a very special and romantic ambience to Tudor gardens.

Mazes and labyrinths

Mazes and labyrinths symbolise man’s tortuous journey towards salvation. The first mazes and labyrinths appeared as designs worked into church pavements in the 12th century. In the 16-17th century they became a popular ornamental feature, however at this point they were only knee-high. The Tudors loved mazes but not because of pleasure, but because of the scents of herbs and flowers that were planted between the hedges. High mazes only arrived in the late 17th century when William and Mary commissioned the first one in 1690 at Hampton Court. This is the oldest surviving example of a high puzzle maze in England. The difference between the maze and labyrinth is that a maze has multiple paths which branch off and don’t lead to the centre, whilst a labyrinth has only one path and no dead ends so you can’t get lost.

Knot-gardens

Knot gardens became fashionable during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign. These had a square shaped frame and different herbs and aromatic flowers were planted in them in geometrical forms. Later the edges or the frames of the garden were planted with box hedges and the paths in between were laid with gravel. A small garden might consist of one compartment, while large gardens might contain six or eight compartments.

Whenever I have a peek at a Tudor banqueting house, I always think how lovely it would to have one as a study or reading room or perhaps as a studio. Somehow, I can’t imagine using a beautiful banqueting house purely for eating desserts… How about you?

Comments (0)